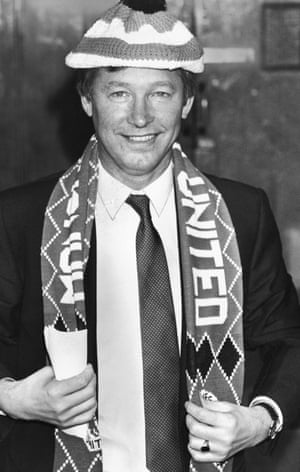

Alex Ferguson up close: sometimes difficult, always great

Sir Alex rewarded those covering his thrilling Manchester United teams with the best of times

What do you write in these moments? It isn’t easy and even now, Fergie being Fergie, there is still that slightly unnerving feeling that one day he might go over everything that is written and take issue with any article that reads too much like an obituary for his liking.

Somehow, the image of him holding up one of the offending newspapers, rolling‑pin-style, and threatening to swipe a journalist over the head – trust me, I’ve seen it happen – feels so much more natural than the idea of one of the greats of his profession lying, stricken, in an intensive‑care unit.

The reality, of course, is that nobody can be sure what happens next. For now, it is probably just enough that he has made it through the first 24 hours, that the statement from Old Trafford described his emergency operation as a success and that, somehow, we all expect him to have different powers to the ordinary man.

That’s not really how it works, from a medical point of view, but this is Sir Alex Ferguson we are talking about, not any person, and my mind goes back to the promise he made to us on his 65th birthday.

Ferguson was on great form that day. He talked about using his bus pass on “the 4A to Govan Cross”. He seemed to like the bottle of pinot noir that had been bought for him and, locked in one of his battles with Chelsea at the time, the card expressing the wish that it was “better than the paint-stripper Mourinho gives you”. He made it sound that age, not José Mourinho, was now his toughest opponent but he also made it clear he was ready to meet the challenge head-on. Then he raised himself off his seat and headed for the door, wearing a sunrise of a smile. “You haven’t got rid of me yet,” he called over his shoulder. “No matter how many times you’ve tried. I’m still here. You lot will all be gone before I am. I’ll see you all off.”

He always did like to have the last word. Even when his Manchester United team won the European Cup on that sweet-scented night at Barcelona’s Camp Nou in 1999, Ferguson made sure to gather all the first editions of the newspapers so he could scrutinise the early critiques. Back then, the first editions had to be off-stone so early that nine-tenths of the match reports were written during the game – ie United losing – and filled with paragraph after paragraph pointing out where Ferguson had got it wrong.

The later editions were all glory-glory-Man-United rewrites courtesy of the stoppage-time goals from Teddy Sheringham and – football, bloody hell – Ole Gunnar Solskjaer. But guess which ones Ferguson pored over? He took a lot of pleasure reciting the more fault‑finding lines when we shuffled into the pressroom at United’s training ground on the first week of the following season.

People ask what he is like and the truth is that he always kept us a long arm’s length away. We would have loved to break bread with the man, clink wine glasses and feel his trust during those years when he turned United into the most prolific trophy‑grabbing machine in the game.

That wasn’t actually how it worked and it wasn’t fun, to say the least, in the periods when he was convincing himself that every question was being laid like a trap. Yet they were still, overall, the best of times for the football writers on the Old Trafford patch and he wasn’t always “slamming” or “blasting”. When the shackles came off, when he disarmed his audience with long, impassioned homilies about football, politics or the world in general, those were the moments when you were reminded that time in his company was a privilege, both rewarding and fascinating.

Plus, there was another Ferguson, very different to how he appears on television or in the press. He wasn’t always living up to the caricature: the flint-faced authority figure, menacingly chewing his gum, pointing to his stopwatch, little red puffs of toxic smoke coming out of his ears. The time, for example, one of the journalists on his patch, John Bean, suffered a heart attack and the first contact he had from the outside world was a nurse bringing him a bunch of flowers, with Ferguson’s spidery handwriting asking “What have you been doing to yourself, you silly old tap dancer?”

This is the side of Ferguson that his friends and colleagues cite – the soft-focus Ferguson who was capable of overwhelming generosity and kindness. Often, when his mobile phone was clamped to his ear, it would be Ferguson offering words of encouragement to a struggling manager. There were invitations for a sacked manager or coach to help him out in training for a few days. When he heard Paul Hunter’s cancer had spread he sent a video message to the former British and twice Welsh Open snooker champion telling him he should be proud of everything he had achieved and praising him for his bravery. He had never met Hunter but that detail, as far as Ferguson was concerned, was irrelevant.

Or how about the story David Meek, the former Manchester Evening News correspondent, tells about being diagnosed with cancer in 2003 and having to break the news to Ferguson that he wouldn’t be able to ghost-write his programme notes? “He wanted to know why and when I told him I was going into hospital he looked me in the eye and said exactly what I wanted to hear: ‘You can handle it.’ There was a huge bouquet waiting for me at the hospital. Then I was convalescing at home a week later and, out of the blue, the phone rang. There was no introduction. He didn’t even say who it was. A voice just growled down the line: ‘The Scottish beast is on his way.’ He was at my front door 20 minutes later.”

This isn’t a love letter, by the way. There were times, frequently, when it was difficult to square Ferguson’s more appealing characteristics with his other traits. Even introducing yourself had its challenges. His eyes would squint, his brow crease. “Who are you?” he might demand, staring with those rheumy, impenetrable eyes. One reporter, in his 30s, was sent up from London. “Jesus Christ, do they get them straight from school these days?” came the response. Ferguson never used to have TV crews in his press conferences. With no cameras present, there were some extraordinary moments in that pressroom.

He could be dictatorial and hostile, his temper could go off like a car alarm and, in the worst moments, it seemed like United were the hardest club in the world to cover. Every successful manager has to be, at times, a bit of a bastard. And Ferguson was the best in the business when it came to that part of the job, too. He had us all on the run at various times – journalists, referees, rival managers, the Football Association; everybody.

Yet here’s the thing: you always knew you were in the presence of greatness. No one managed at the highest level for so long. Nobody beat the system the way he did before retiring in 2013,after winning his 13th Premier League title. Ferguson lasted 26 years on that epic grind of 6am starts, getting by on unfeasibly little sleep, and winning so many trophies they once had an advert for MUTV, the club’s subscription channel, that showed a skip outside Old Trafford, filled with empty cans of silver polish.

Ferguson outlasted 24 managers at Real Madrid, 18 at Chelsea and 14 at Manchester City. He saw off four prime ministers – Thatcher, Major, Blair and Brown – and would undoubtedly have liked to add Cameron to that list. Matt Busby was 62 when he left Old Trafford. Bill Shankly quit Liverpool at the age of 60. Bob Paisley lasted at Anfield until he was 64. Brian Clough was 58 when he closed his reign at Nottingham Forest. Ferguson was 71, with a pacemaker in his chest and a hip replacement on the calendar, when he cut himself free and it was still a profound shock. The Daily Telegraph once called him The Man Who Couldn’t Retire.

Where to start with his achievements? It isn’t easy keeping count of all the trophies he accumulated since starting out in management, in 1974, at East Stirlingshire (where he inherited eight players and no goalkeeper). There were 49 in total and, to put it in context, Ferguson’s 13 English championships is the same number that Arsenal, the third most successful club in the country, have managed in their 132-year history. For United, there were also two European Cups, two Intercontinental World Cups, one European Cup Winners’ Cup, five FA Cups, four League Cups, on Super Cup and 10 Community Shield wins. Manager of the year? Ten of them. Manager of the month? Twenty-seven. As success goes, it borders on ludicrous.

Yet Ferguson’s hold over the sport went further than just his trophy count. He is, without any doubt, the most signifiant and influential football person in the Premier League era, winning the first of his championships in the year it all started. Ferguson was the man who gave us the famous quote, expletive removed, about knocking Liverpool off their perch.

For Aberdeen, Ferguson proved it was possible to take on, and defeat, the Old Firm, winning the Scottish league title on three occasions, plus an assortment of other trophies and that never‑forgotten victory against Real Madrid in the Cup Winners’ Cup final.

He moved to Manchester in 1986 to take over a side that had not won the league since 1968 and it has gone down in United folklore how, after trying unsuccessfully for three years to put that right, a banner appeared at Old Trafford calling for his removal with the words: “Three years of excuses and we’re still crap – ta ra Fergie.” When Ferguson retired, the fan with the spare bedsheet and pot of paint produced another banner: “Twenty‑three years of silver and we’re still top, ta-ra Fergie.” Ta-ra, indeed. The word legend gets used too often in football. Not in this case. To many people, he was the legend, the most successful manager in the history of British football.

The most feared, too. Ferguson’s temper was also the stuff of legend and unless you have seen the “hairdryer” on full blast, it is difficult to find the words that adequately describe it. Whatever you imagine, it is worse, much worse. They gave it that nickname because of the way he used to stand in front of the recipient and lean in so close, shouting with such force – it was like being in a wind tunnel.

Ultimately, though, he will be remembered for putting out teams that played football of rare brilliance. Was there a better sight in England than Manchester United chasing a game? Did any other team score as many late, heroic goals? Ferguson wanted his teams to win prizes in a certain, thrilling fashion. They were one of those teams that made you quicken your walk on the way to seeing them. You had to see them.

They have never played so beautifully since he left and it probably says everything about his reach that the Chicago White Sox and the NBA are among those to send tributes and sympathy messages. The clubs that once feared him – Liverpool, Arsenal, Manchester City and all the rest – have done the same. And now we wait for the next update while, in another sense, maybe it would be better if there was no more news.

Was it only last weekend that we saw him by the side of the Old Trafford pitch, embracing his old adversary Arsène Wenger with a slightly awkward man-hug, beckoning for Mourinho to join the photo-opportunity and smiling into the cameras? The thought occurred that day that he was looking well, 76 years young. His hair, once chestnut, has been grey for some time, the cheeks rubicund, but everything we have heard about his retirement has suggested a man making the most of his adjusted priorities, visiting new places, keeping busy, still so energised and driven with that unstoppable enthusiasm for life. And then this. Fergie, bloody hell.

Since you’re here …

… we have a small favour to ask. More people are reading the Guardian than ever but advertising revenues across the media are falling fast. And unlike many news organisations, we haven’t put up a paywall – we want to keep our journalism as open as we can. So you can see why we need to ask for your help. The Guardian’s independent, investigative journalism takes a lot of time, money and hard work to produce. But we do it because we believe our perspective matters – because it might well be your perspective, too.

I appreciate there not being a paywall: it is more democratic for the media to be available for all and not a commodity to be purchased by a few. I’m happy to make a contribution so others with less means still have access to information.Thomasine, Sweden

If everyone who reads our reporting, who likes it, helps fund it, our future would be much more secure. For as little as $1, you can support the Guardian – and it only takes a minute. Thank you.

No comments:

Post a Comment